Kiln use – How to properly use a Kiln

Preparing Your Kiln

Before you begin classes it is always good to do a few things to insure a successful year of firing.

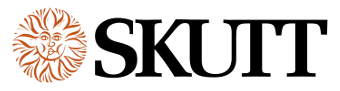

Vacuum Out The Kiln

Throughout a year of firing your kiln gets loaded with brick dust and bits of clay and glaze. All this debris sitting on your elements can cause them to burn out early and cost your budget money you could have saved with just a little housekeeping.

Quick Safety Inspection

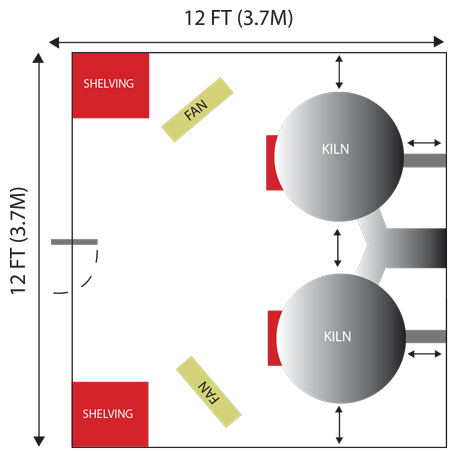

Who knows what could have gone on in your kiln room when you were away for summer. It’s always a good idea to take a little walk around and look for obvious safety hazards like loose screws, flammable material around the kiln, power cords touching the kiln and damaged or missing hardware.

If you are new to the school or have a new kiln room you will want to make sure that there is no sprinkler right above the kiln. If there is you will want to notify your administrator so they can verify that it was installed properly with the knowledge that a kiln would be firing directly under it. Sprinkler heads can be fitted with high temperature fuses for these types of installations. If they are not fitted with the correct fuse you could set them off.

Test Fire The Kiln

Wouldn’t it be great to find out if something was wrong with the kiln BEFORE it was too late to do something about it? Load the kiln with shelves just like you were loading it with ware but without the ware. Place 04 Self Supporting Witness Cone (available at any ceramic supply store) on each shelf 2 inches from the kiln wall. Be sure to place one next to the thermocouple also 2″ from the thermocouple and kiln wall.

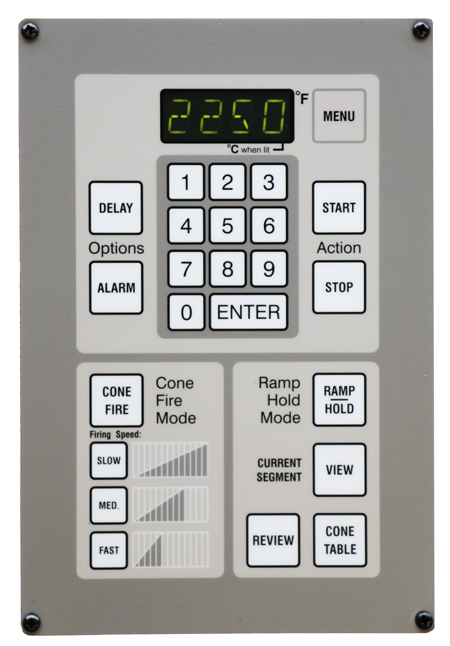

Turn on your downdraft vent if you have one and make sure any additional room vent you have is operating. Program a Medium Speed 04 ConeFire program, press review to make sure you entered the program correctly and Press Start. Listen to the control box. You should here the relays clicking on and off and see the temperature on the display begin to rise. If you here any strange noises or smell smoke press stop and call a technician. (Note: Brand new kilns or kilns with freshly replaced elements will smoke a little from residual oil on the elements. This is normal and the smoke should clear after a few minutes.)

After the kiln is done firing the display will flash CPLT for complete alternately with the current temperature of the kiln, and the amount of time the kiln took to fire. Write this time down. It should be fairly close to 7.5 hours. If it is taking 8.5 hours or longer, you may need to call a technician to diagnose potential problems. If you come back to the kiln and there is an error message, write down the message and contact your technician.

Once the kiln has cooled to room temperature open the lid, remove your shelves, and inspect your cones. They should all be bent anywhere from 20 degrees to the tip just hanging above the shelf. If the cone next to the thermocouple is touching the shelf, it is a good indication that you need to change your thermocouple. If a cone does not bend at all , it may indicate the element or relay in that section is beginning to wear.

Loading the Kiln

How you load your kiln can play a big part in the success of the firing. We have a great video which describes in detail all the things you need to consider when loading your kiln. Watch the video and let us know if you have any questions. Here is a list of some of the basics:

- Never load wet ware.

- Maintain proper clearances: 2″ from the lid, 1 inch from the kiln walls, at least 1″ from the bottom, and 2″ from the thermocouple.

- Spread the mass uniformly throughout the kiln.

- If certain areas of the kiln tend to fire cooler, load them less densely on future firings.

- Make sure you always have at least one element radiating between the shelves.

- When using half-shelves, leave a 1/4″ gap between them if they are side by side and stagger them whenever possible (see image).

- Use Self-Supporting Pyrometric Cones to monitor the results of the firing.

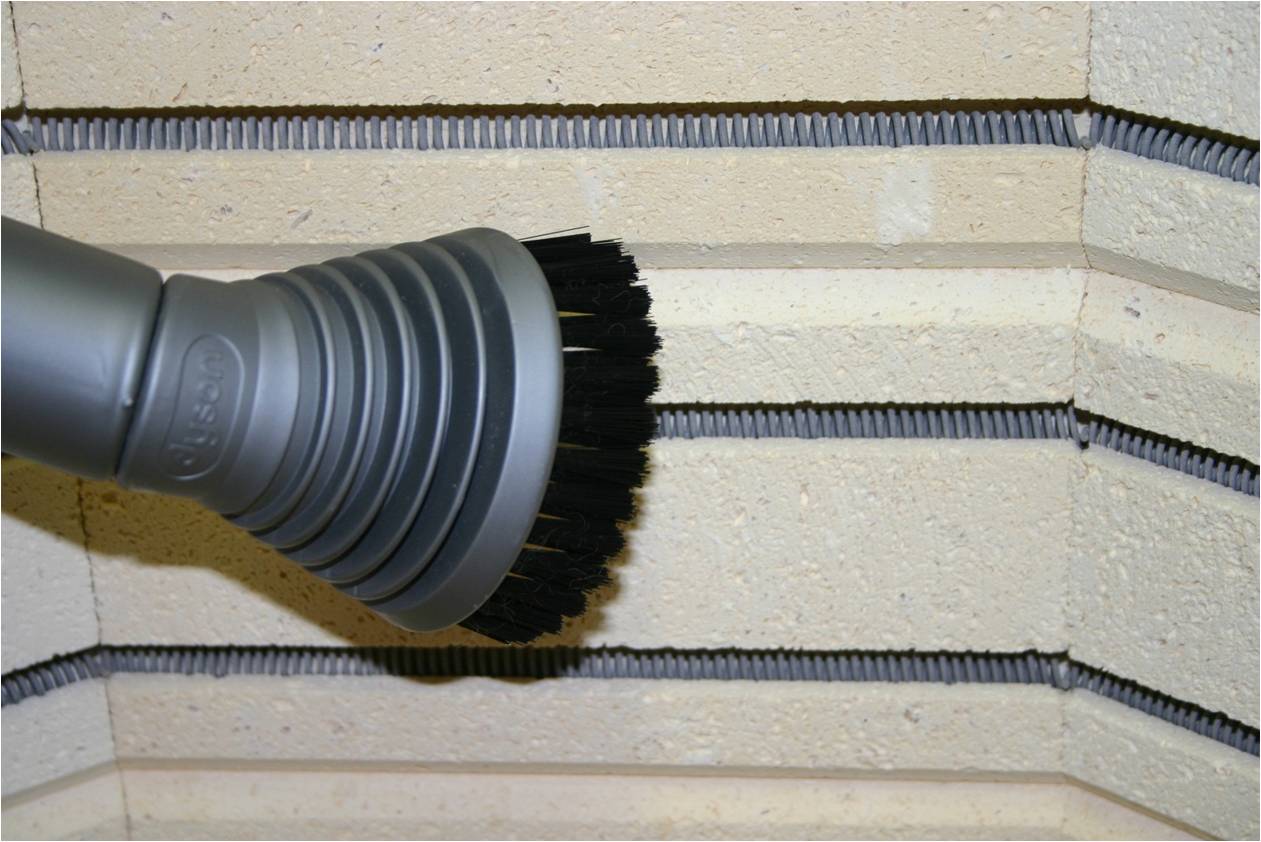

Programming ConeFire Mode

Your controller has two firing modes, ConeFire and Ramp/Hold. ConeFire is by far the easiest and most common firing mode used in Ceramics. Ramp/Hold is used primarily to fire specialty glazes or to fire non-ceramic pieces like glass or metal clay. Programming a kiln may seem intimidating, but once you do it a few times you will find that it is really quite easy.

We put together a video which takes you step by step through programming your kiln. If after watching the video you still have questions feel free to call us and we would be happy to walk you through your first firing.

Unloading the Kiln

The number one rule in unloading your kiln is BE PATIENT. No matter how long you have been doing ceramics, opening the kiln after a glaze firing is always exciting. Too often people will get a little impatient and try to open it too soon. Wait until the kiln has cooled below 125°F to open your lid. If you open it to soon, the glaze could craze and will no longer food safe since bacteria can grow in the small cracks.

As you unload the kiln make notes in your firing log regarding how the cones looked, how the kiln was loaded, how the ware looked and how long the firing took. This will help you make adjustments on your next firing.

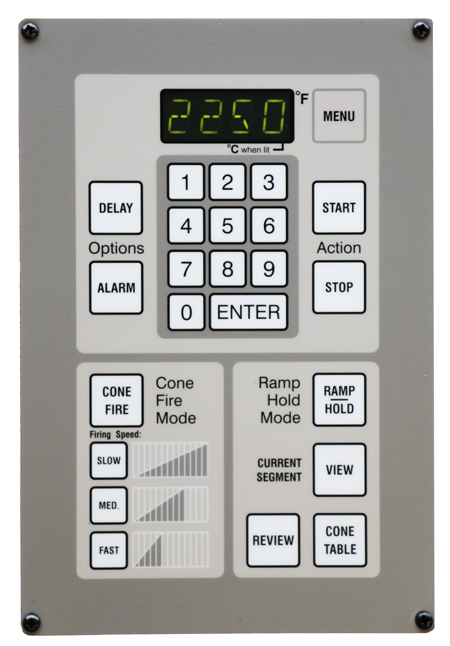

Loading Glass

Fusing and slumping has really taken off in classrooms all across the USA and Canada. For years teachers thought they needed a special glass fusing kiln to work with glass in their curriculum. Not so! Read the article below to see how you can load and program your ceramic kiln and get great results.

Firing Glass in a Ceramic Kiln

Programming Ramp/Hold Mode

Your controller has two firing modes, ConeFire and Ramp/Hold. ConeFire is by far the easiest and most common firing mode used in Ceramics. Ramp/Hold is used primarily to fire specialty glazes or to fire non-ceramic pieces like glass or metal clay. Programming a kiln may seem intimidating, but once you do it a few times you will find that it is really quite easy.

We put together a video which takes you step by step through programming your kiln. If after watching the video you still have questions feel free to call us and we would be happy to walk you through your first firing.

Safety

Kilns are used safely in 10’s of thousands of homes and schools all over the world everyday. With a little bit of common sense and good understanding of your kiln you can easily avoid any problems. Be sure to read your manual cover to cover before operating your kiln and pay special attention to the section in the beginning on safety. Click the links to access a copy of the manual and be sure to also watch the video on setting up your kiln room to create a safe and efficient studio.

Ceramics 101

You could spend a lifetime building your knowledge of ceramics, and many people do. It is a fascinating medium with infinite possibilities for exploration. In this section we hope to give you the bare bone basics to help you get started. For additional information and training you can find classes in your area by visiting www.kilnarts.org.

Choosing Your Clay and Glaze

There are many types and colors of clay and glaze. Most classrooms use what is called “Earthenware” clay. This is a clay body that is reasonably priced, easy to work with and fires to a lower temperature which means less wear and tear on your kiln. All clay and glaze have “Cone Rating” associated with them. This refers to the temperature range to which they are to be fired. There are many choices of glaze types to use. The important thing is to choose a glaze that is fired at the same temperature range as your clay. Generally you are looking for clay and glazes that are in the Cone 04 to Cone 06 range. The cone rating will be printed on the box of clay and jar of glaze.

Shaping the Clay

Most beginning ceramic classes don’t have the time necessary to teach the students how to throw on a potter’s wheel, so they generally make hand built pieces. These can be pinch pots (made by pinching the clay, coil pots (made by joining rolled coils of clay), slab work (made by joining pieces of clay that have been rolled out flat) or simply by making little free-form sculptures. What ever your project type, it is best to start small and make sure the clay is not too thick. This will help ensure the projects will make it through the kiln firing ok.

Drying the Clay

Place the greenware (unfired clay) on a drying rack in a well ventilated area. It is very important to make sure the clay is completely dry before you place it in the kiln. Water turns to steam at 202 °F. if there is still moisture in the clay in can actually explode the piece as the steam tries to escape. This is not dangerous but it can cause damage to the kiln and other pieces in the firing. Hold a piece up to your cheek to feel the temperature. If it is still cool to the touch it needs more drying time. Usually a week is enough time.

The Bisque Firing

The bisque firing is where the projects transform from clay (greenware) to ceramics (bisque). Prior to this first firing they are very fragile so handle them with care while you are loading the kiln. Program the kiln to run a Cone 04, Slow Speed, ConeFire Program. if you have the option of “Preheat” on your controller, a 2 hour preheat is good insurance to prevent exploding pieces. This will take about 12 Hours to fire to temperature and another 12 hours to cool (depends on size of kiln).

Applying the Glaze

The number one rule in glazing is NO GREASY FINGERS! make everyone wash their hands before the handle the bisque. If the pieces sit around for awhile before you get a chance to glaze them you may want to sponge them off to make sure all the dust is removed. There are many different types of and colors of glaze to choose from. Some are specially formulated to look relatively the same color as the fired glaze but many look completely different after they are fired. it is helpful to download a color chart from the manufacturer so the students have a clear idea of how it will look after it is fired. The amount of glaze you brush onto a piece can be very important, too much and it looks washed out and too much and it runs all over your kiln shelf. Again, the manufacturers website should give tips on application.

The Glaze Firing

The glaze firing is the most exciting part of the process for a lot of people. If you can have the students take a look at the loaded kiln before the firing and then again when you open the lid. This is where the magic happens. When loading the kiln it is important to handle the pieces carefully so the glaze does not come loose. Be sure to wipe off any excessive glaze that may touch the shelf or be applied to thick. If they have glazed the bottoms of the piece you will need to place them on special stilts designed to hold ceramics while they are fired. Program the kiln to run a Cone 06, Medium Speed, ConeFire Program. This will take about 8 Hours to fire to temperature and another 12 hours to cool (depends on size of kiln).

Glass 101

The following guidelines just scratch the surface of the knowledge base associated with firing glass. We

highly suggest you take a firing class from your local distributor. If classes are not available in your area, there are numerous books available on the subject that can be found at bookstores and on the internet.

What is a Firing Program?

Glass is very sensitive to changes in temperature below 1000 °F. If it is heated or cooled too quickly through

certain temperature ranges it creates stress within the glass which can

cause breakage. Firing programs are used to control these temperature

rates and limit the amount of stress created within the glass as well as

create the desired effect on the glass.

A firing program is composed of one or more firing segments that

dictate the heating or cooling rate throughout the program. Each one of

the lines in the chart represents a segment or hold time within a segment

and the slope of the line represents the rate of firing. A firing program

is either entered into a kiln controller or on kilns without controllers it is

replicated by turning up and down temperature switches.

Type of Glass

The art of firing glass has been around for centuries however, comparatively speaking, it has only been

recently that companies have begun manufacturing glass specifically designed to fuse together. Glass, like most

everything on earth, expands when exposed to heat and contracts when it is cooled. It expands at a measurable

rate, known as the COE, or coefficient of expansion, and as it becomes liquid it flows at different rates which is

referred to as it’s viscosity level.

These variables and a host of others must be carefully managed to create glass that can be fused together

without crazing, cracking, warping, or breaking. Always consult with your supplier of glass to determine if the

glass you wish to fuse is compatible.

Heatwork

Heatwork is a term used to describe the relationship of time and temperature and their combined effects on

glass. To a certain extent the two are inversely related. This means that the higher the temperature the less time is

needed to create the same effect and likewise, the lower the temperature the more time is needed.

This concept becomes most useful at the “Working” temperature range of glass. This is the temperature

range where the glass is fused, slumped or sagged. Most fusing glass will fuse between 1450 F and 1480 F. It

is possible to get the same results (or the same amount of heatwork), by bringing the kiln to 1450 F and holding it

at that temperature for 30 minutes as you would by bringing the kiln to 1480 F and holding it for only 10 minutes.

There may be other factors that make you choose one working temperature over the other such as the thickness of

the project.

Size and Mass

The size of the piece is one of the most influential factors for creating a firing program. One of the keys to

successful heatwork is having the entire piece go through critical temperature ranges at the same moment. When

a piece is thick it takes longer for the center to heat up than it does the outside of the piece. When it is a large

diameter, slight differences in temperature throughout the chamber of the kiln can cause the piece to expand at

different rates.

The key to firing larger and thicker pieces is to slow the firing rates through critical temperature ranges.

Determining how slow is often a trial and error proposition therefore it is best to start with a conservatively slow

program. More projects are ruined by going too fast than too slow.

Critical Temperature Ranges

A “Critical Temperature Range” is any temperature or temperature range in the firing cycle that has a high

level of potential for limiting the success of the project. Limited success can be expressed as overfired, underfired,

breakage, devitrification, or bubbles just to name a few. It can be argued that there are numerous critical

temperature ranges. To keep things simple we are going to discuss the primary four: Heating Range, Process

Range, Pre-Annealing Cooling Range, and Annealing Range.

Heating Range

The Heating Range goes from room temperature to the first set of data in the Process Range. The only

concern during this range is heating the pieces too fast without adding steps to the program. Steps are hold

periods at designated temperatures that allow the piece to balance out during the firing. Small pieces can

normally be heated as fast as 800 F./Hr. as long as steps are added. With larger pieces you will want to slow

the rate and possibly add additional steps depending on the size of the piece.

Process Range

The Process Range is the temperature range where the material begins to visibly change. It is this stage

that determines the final shape of the piece. It is often a good idea to add a pre- Process Range segment to

slow the kiln down before entering the Process Range. If the kiln is firing too fast into the process range it is

possible to overshoot your goal temperature.

During the Process Range temperatures and hold times are key. If you are unsure of the desired peak temperature

you may want to start on the low end of the range with a longer soak. This will help insure that thicker

pieces receive the proper heatwork throughout the entire piece.

Pre-Annealing Cooling Range

After the process range is through, it is desirable to cool the piece quickly for several reasons. The first

reason is to stop the heatwork. This is especially important on a project such as a less then 100% fuse or a

drop mold.

The second reason is that an undesirable reaction known as devitrification can occur during this cooling

period if the kiln is cooled to slow. Devitrification is a scummy white crystallization on the glass surface that is

difficult if not impossible to remove. Be sure to slow down the cooling before you enter the Annealing Range.

Opening the kiln lid to increase the rate of cooling, while practiced, is not always recommended. On certain

models the thermocouple is in the rear of the kiln and the temperature from front to back can vary greatly

causing part of the piece to enter the annealing phase before the part in the rear.

Annealing Range

The final critical range is the Annealing Range. Every piece of glass has an annealing point, this is a

point in the cooling cycle where the molecules in the glass realign themselves into a solid and stable form. It is

very difficult to know exactly where that specific point will be, so during this period it is critical to fire the kiln at

a slower rate throughout the range.

Our pre- programmed firing schedules in the Glass Fire Mode anneal from 1000 °F to 750 °F which

should be adequate for most stained glass. By incorporating such a broad range the risk of breakage is limited.

Be sure to keep the lid or door of the kiln closed until the kiln reaches room temperature. Opening the lid

too soon can cause pieces to break.

Firing Processes

There are many different processes or techniques used for manipulating glass with heat inside a kiln. In this

manual we will focus on two, Fusing and Slumping. Other techniques include but are not limited to Drop Molds,

Pate de Verre, Casting, Painting, and Combing. For more information on using your kiln with these techniques

please consult your glass supplier.

Fusing

Fusing is the process of joining 2 or more pieces of glass together by the application of heat. This glass can be in the form of sheets, stringers, frit or a host of other forms. There are different degrees of fusing. You may want to fuse glass so it sticks to another piece of glass without deforming. This is known as a “Fuse to Stick”. If you were to apply more heatwork to the piece the edges would round slightly. This is known as a “Tack Fuse”. A “Full Fuse” is created when the pieces have melted completely together and are 1/4” thick. A “Texture Fuse” is any point in-between a Fuse to Stick” and a “Full Fuse”. There is a temperature range at which glass can be fused. The point at which it begins to fuse is influenced by the rate at which the temperature is climbing when it reaches the fusing range. Most fusing glass will begin to fuse between 1400 F and 1480 F. Remember that heatwork is a function of time and temperature. Starting with glass that has been determined to be compatible is only the beginning to a successful fusing or slumping project. The temperature and various temperature rates in a firing program must be designed to the specific needs of the project you are creating. The size, thickness, shape, and type of glass all must be considered when designing a firing program. As a precaution you may want to provide a dam or barrier around the glass when fusing more than 2 layers. With more than 2 layers, the glass will spread until it finds a level of 1/4” and could possibly flow into another piece or off the shelf.

Slumping

Slumping can be defined as the controlled bending of glass under the influence of heat and gravity within a kiln. This is generally done over or into a mold. Molds can be made out of a variety of different materials and can be found at art glass supply businesses. When slumping, it is necessary to take into account the shape of the mold, the thickness of the piece, and the degree of heatwork desired. Gravity plays a very important role in slumping, especially slumping over a mold as opposed to into a mold. If the shape of the mold dictates that the unbent glass is largely unsupported, the weight of the unsupported glass will pull the glass over the mold quicker than if only a small portion is unsupported. A thin piece of glass will bend quicker than a thick piece of glass. A thick piece of glass requires more Hold time in the final segment of the process phase. In some cases the artist may want to control the amount of bend by visually inspecting the kiln. When the proper amount of heatwork is reached the artist can begin annealing. Slumping projects that receive too much heatwork can take on unwanted texture from the mold or in extreme cases fuse to a puddle.